How Self Employed American Expats Can Escape the FICA Tax Trap

This is educational, not individualized tax advice. Consult a qualified professional before restructuring. If you would like to work with us, please reach out via DM at @BowtiedBrazil

If you're a self‑employed American who’s moved abroad, you’ve probably discovered the painful truth: that 15.3 % self‑employment tax still follows you, no matter the time‑zone

Many expats focus on the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) and get blindsided when their accountant explains that FICA still applies to their $250k of consulting/insert other type of digital income. With 2025 figures, that means about ~$30k in self‑employment tax, before regular income tax kicks in.

Let’s break down why FICA pursues you globally and exactly how to structure your business to reduce or potentially legally eliminate it

The Self‑Employment FICA Problem

When you’re self‑employed in the U.S., you pay the full 15.3 % FICA burden (12.4 % Social Security + 2.9 % Medicare). Employees split that bill with an employer; single member business owners don’t get that luxury (although you can get a deduction as the owner for the employee expense portion fo that)

Here’s the expat trap: FICA liability attaches to you personally. A U.S. employer must withhold FICA on your wages even if you’re coding from Colombia. And if you’re self‑employed, you owe self‑employment tax on all your net earnings, regardless of where the work physically happened. A single billable day back in a U.S. coffee shop doesn’t just tax that day’s revenue, it means the whole year’s net self‑employment income is potentially in play (called “tainting”).

Your only automatic relief is the Social‑Security wage base ($176,100 for 2025). Above that, the 12.4% Social Security portion drops off, but Medicare’s 2.9% stays, and the 0.9% Additional Medicare Tax kicks in once your combined wages + self-employment income exceed $200k (single filer).

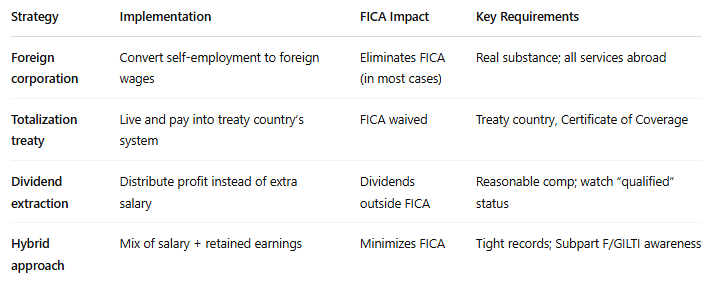

The Foreign Corporation Structure for Self‑Employed Expats

For consultants, freelancers, and digital entrepreneurs, the most effective move is to convert your sole proprietorship or single member LLC (not applicable to LLCs taxed as S-corps) into a bona‑fide foreign corporation and become its employee.

Typical roadmap/steps

Form a corporation in a tax‑neutral jurisdiction (Nevis or BVI are common)

Have clients contract with and your foreign company directly

Run real payroll through the foreign entity

Pay yourself a salary as an employee

Perform all services physically outside the United State

Under most circumstances, wages paid by a foreign employer for services performed abroad aren’t subject to U.S. FICA.

(But keep in mind a few exceptions: if the foreign company elects §3121(l) coverage, or is treated as a U.S. employer under special common‑control rules, FICA can still pop up (rare in the cases we’re discussing here))

Making Your Structure Audit Proof

Paper companies invite paper results. Create economic substance (discussed in previous stack) by:

Signing a real employment agreement between you and the corporation

Running actual payroll (and paying whatever local social security equivalent tax your host country may impose)

Keeping separate corporate and personal bank accounts

Documenting board resolutions for major decision

Logging where every workday is performed (never billable work while on U.S. soil)

Invoicing exclusively through the company (ie no direct wires to your personal account)

Slip on any of the above and the IRS can recast the whole setup as self‑employment income, bringing FICA back in.

The FEIE Reality Check

The FEIE now shields about $130k of foreign wages for 2025. It does nothing against self‑employment tax. Once you’re an employee of your foreign corporation, though:

Your paycheck is foreign wages, not self-employment income for US FICA tax purposes

FEIE (and possibly the foreign housing exclusion) can offset some or all U.S. income tax

FICA vanishes (assuming you’ve refined the structure correctly)

That’s the potential “double win” too many expats miss when focusing only on FEIE

Totalization Agreements: A Simpler Door When Available

The U.S. maintains about 30 totalization agreements (2025 count) to prevent double social‑taxation. If you’re self‑employed and living in one of these treaty countries and paying into its social‑security system, you can usually waive U.S. self‑employment tax with a Certificate of Coverage.

No treaty? No relief. So destinations such as the UAE, Thailand, or Panama (no totalization agreements even th ough Thailand has a treaty) require the foreign‑corporation route even if the local system has little or no social tax

The Dividend Angle for Owner‑Employees

FICA targets wages and self‑employment income, not dividends. With a properly structured foreign corporation:

Pay yourself a reasonable salary to cover living costs (and satisfy “reasonable compensation”)

Leave surplus profits in the company

When convenient, distribute dividends

Caution: Dividends from many zero‑tax jurisdictions aren’t “qualified,” so they’re taxed at ordinary rates plus the 3.8 % NIIT, still better than adding 15.3 % FICA on top, but not as sweet as 20% qualified‑dividend treatment. Also remember: if the company is a CFC, Subpart F and GILTI rules can apply no matter how you distribute or don’t distribute cash.

Real‑World Playbook

Successful six and seven- figure expats often:

Form a real foreign company in a tax‑advantaged spot

Redirect every client contract and dollar to that entity

Pay themselves $50–80k in salary via proper payroll

Accumulate remaining profit in corporate accounts

Pull dividends in lower‑income years or reinvest

Visit the U.S. strictly as a tourist and do no billable work when visiting

Track travel/work locations obsessively (written/online)

Audit triggers remain: co‑mingled funds, weak corporate formalities, U.S.‑sourced work, or sloppy international filings

Seeing the Bigger Tax Picture

As we touched upon, FICA reduction is only one piece. You and your advisor must always balance the following considerations as well:

Subpart F income on passive earnings.

GILTI on active profits left in a CFC.

State “sticky‑resident” taxes if you never cut ties.

Host‑country tax on wages, dividends, or corporate income.

Even with these layers, the foreign‑corporation strategy often delivers the best net outcome for high‑earning solo biz owners

Bottom Line

If you’re self‑employed abroad and clearing six figures, a legitimate foreign‑corporate structure can save you tens of thousands in FICA every year. Implement it carefully, document everything, and make sure the rest of your U.S. (and local) tax obligations are squared away